Nose bleeds are a less frequent tradition in the Gutowski family now as a team of doctors work together to treat their abnormal blood vessels caused by hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

5:00 AM

Author |

Arthur Gutowski and his son, Arthur Jr., share not only a name, but a rare hereditary blood vessel disorder that can cause severe nosebleeds, costing them as much as a cup of blood at a time.

"My mom and uncle had nosebleeds, my grandma had nosebleeds, I have nosebleeds," says Gutowski, 72, of Dearborn, Mich. All three of his sons, including the eldest, who goes by AJ, have or had experienced them as well. (Chris the middle son, passed away in 2012.)

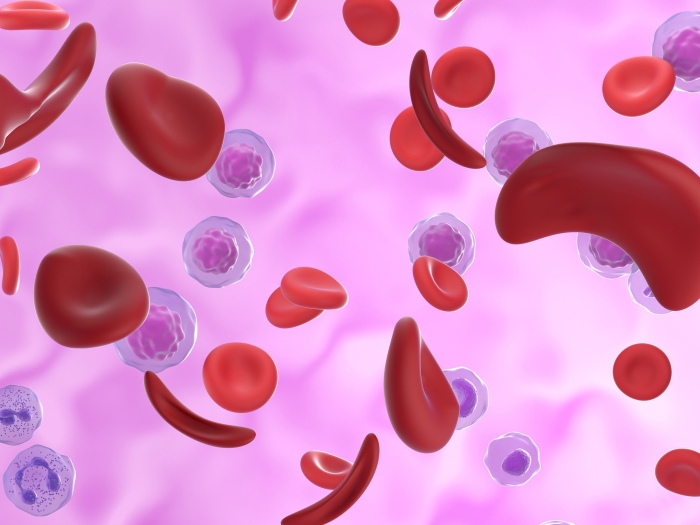

The Gutowski's have hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), a disorder characterized by nosebleeds and fragile blood vessels. It's also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

"Not a lot of physicians know about HHT," says their mutual doctor, Jeffrey Terrell, M.D., a professor of otolaryngology (also known as an ENT, for ear, nose and throat) at Michigan Medicine, so an estimated 90% of people with it go undiagnosed.

Terrell hopes to change that as Michigan Medicine becomes the state's first designated HHT Treatment Center. The honor comes from Cure HHT, a nonprofit dedicated to finding a cure for the disease, and the CDC.

It means an integrated team of HHT experts — including genetic counselors, ENTs, hematologists and interventional radiologists — work together to provide the highest level of care to help patients manage their HHT.

"Patients used to drive to Cleveland or Minnesota to go to such a Center but they have one much closer now," Terrell says.

The designation came with the help of a research grant Michigan Medicine hematologist Suman Sood, M.D. received from the Department of Defense and the CDC that combines treating people with HHT and hemophilia, an inherited disorder where the blood can't clot because of missing proteins in the blood.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

HHT is a gene mutation that causes blood vessels to form abnormally. While the cure remains elusive, it affects about 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 10,000 people. For the Gutowski family, it had a 100% frequency rate.

Nosebleeds are all in the family

The nosebleeds experienced by the Gutowski family and others with the disorder frequently causes their hemoglobin numbers to plummet from a healthy adult male range of 12-18 to 4-6, making them tired, dizzy, short of breath and anemic. Before they started seeing Terrell, simple triggers for bleeds were yawning, sneezing and bending over to tie their shoes.

"I learned to sneeze with my mouth," AJ says. So does his father.

AJ was in sixth grade taking a quiz when he believes he got his first nose bleed, which is a typical age for the disease to emerge. "I knew at the time something was off but I knew my dad and grandma had nose bleeds, too," says AJ, 51, also of Dearborn. It was his normal.

HHT patients tend to have two types of blood vessel abnormalities. The smaller ones emerge on the skin, appearing as red or purple dots the size of a pinhead or elaborate spider veins. They're called telangiectasia and are found on the hands, face, mouth lips or inside the nose. The larger blood vessel abnormalities, arteriovenous malformation (AVMs), hide elsewhere in the body, but favor the nose, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, brain and liver. They can be life threatening. The brain AVM, for instance, can cause a stroke. The Gutowski's have liver and gastrointestinal AVMs, along with telangiectasia.

Symptoms change with age

HHT evolves through the years. At first, the elder Gutowski's only symptom was nosebleeds and another spot on his liver, but when he started getting tired all the time, Terrell and his Michigan Medicine colleagues, including Sood and gastroenterologist Neil Sheth, M.D., looked closer. Gutowski had new AVMS in his gastrointestinal tract and they were bleeding.

Sheth used laser treatments to stop the flow and Sood gave Gutowski iron transfusions so he could resume his active life. For his nose vessels, he is on Avastin, a chemotherapy drug that's a vascular growth inhibitor.

"For a while there he quit doing everything and was mostly housebound because he was out of breath and extremely fatigued by his anemia," Terrell explains. "This past summer he went Up North to fish and travel around. His treatment was life changing."

Gutowski agrees. "The U of M doctors are great," he says.

AJ likes having access to the HHT team of doctors, too. He recently had a procedure to blast a kidney stone and they monitored him with extra vigilance because of his tendency to bleed.

Of all the Gutowski's, AJ has long been the most proactive about his care. He keeps up on advancements and raises funds through his volunteer involvement with Cure HHT. He also drives to Washington University in St. Louis where they have an HHT Center for Excellence. Because he has a long relationship with them, he believes he'll continue to drive eight hours to get his suggested three year scans to make sure his AVMs have remained the same or that no new ones have emerged. In fact, they're the ones who noticed his kidney stone during an abdominal scan.

But having an HHT Center closer to home is comforting, too.

"Dr. Terrell approached me about the new treatments and we talk about the risks and benefits," AJ says. "I think actually over time, I've gotten more effective treatments with much less side effects under Dr. Terrell's care," something he expects to continue as Terrell and the Center's team explore newer, emerging treatments.

Having the same doctor as his father is an advantage, too, AJ says.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device or subscribe for daily updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

"We're able to talk to each other about our care and sometimes we go in together," AJ says.

"It's probably been helpful for the doctors to some extent, too, because they see how the disease is working in both of us. And they're able to connect dots a little bit easier," which translates to better care for both of them.

If you suspect HHT or have been diagnosed with HHT and want to meet with a Michigan Medicine specialist, contact a patient care coordinator at (734) 936-6393.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!